Sometimes books rewire the brain. Even as you read, you know already that, by the time you’re done, you’ll be looking at the world a little differently from now on.

Richard Scott’s second collection, That Broke into Shining Crystals, has this quality. I’ve been reading it for a couple of weeks, on and off, and it’s made a mark. It reframes the way in which you read the world as it explores sexual abuse and its legacies. One of Scott’s epigraphs is taken from Emily Dickinson’s ‘The first Day’s Night had come –’: ‘And grateful that a thing / So terrible – had been endured – / I told my Soul to sing –’. Helen Vendler comments that this poem is, to her mind, ‘Dickinson’s most harrowing depiction of active mental suffering’ but, the way Scott cuts it, we’re left with the singing and not with Dickinson’s more awful second day, ‘a Day as huge / As Yesterday’s in pairs’.

The collection opens with a series of ekphrastic poems – all responses to Dutch still life paintings. When visiting galleries, I’ve pootled past these in search of faces and flesh but ‘Still Life with Rose’, Scott’s response to Margareta Haverman’s ‘A Vase of Flowers’ (1716) and Rachel Ruysch’s ‘Tulips, honeysuckle, apple blossom, poppies and other flowers in a glass vase with a butterfly, on a marble ledge’ (c.1691), has put an end to all that. His sonnet opens with ‘Like a foreskin being pulled back’, translating those floral whorls into an arresting intimacy. Line 3’s ‘dense sweet-meat bloom, coral’d cave’ stuffs the mouth with assonance before we choke on its gutturals. Scott paints a dangerous scene: leaves are ‘serrated’ and thorns ‘prick’ (a double entendre which threatens both physical and sexual harm) but, despite this, the painting offers the possibility of escape. The second quatrain opens with ‘So let me in – where everything is new-born / and crystalline, paused, protected – not that other / world, that high-shine of safety, arranged / and sparkling up like a bower’. However, the volta, something we might expect at the beginning of line 9 intrudes into line 8: ‘Almost every day, / for some moments, I think about him’. Margareta Haverman’s ‘A Vase of Flowers’ might appear to be glossy and wholesome but look again and see the snail at bottom left, and at the discolouration of the leaves below it. There’s something rotten here.

In ‘Still Life with Lobster, Fruit and Timepiece’ the speaker’s eye is drawn to the lobster, to its ‘muscle’, to its ‘exoskeleton’ – but the speaker is unable to complete his sentence before the lobster’s hard man image disintegrates. The second tercet opens with ‘terracotta warrior toy’ and, as we reach the third word, we realise that it’s just an image of toughness, a futile attempt to protect that tender centre. Its carapace belies its absolute fragility and ‘even he ended up on the // table – broken apart, belly / opened – men, / silver, flashing above him’. Perhaps we imagine the silverware as the mise-en-scène for some swanky dinner… perhaps. Or perhaps we see flashbulbs, light rebounding from studio umbrellas in another unspeakable act of exploitation. Who, we ask ourselves, is behind the easel, behind the lens? And who lurks beyond the frame, watching from the shadows?

The second section of Scott’s collection, ‘Coy’, a vocabularyclept, plays with Andrew Marvell’s ‘To His Coy Mistress’. Marvell’s poem is a classroom staple and anthologised for GCSE frequently. The tumescent innuendo of ‘vegetable love […] vaster than empires’ is always good for a giggle. However, Scott’s epigraph, taken from Gemma Carey’s No Matter Our Wreckage wiped the smirk from my face: ‘Many people still don’t know what grooming really is, beyond ‘something people do to children’. They don’t know what it looks like, so to speak’. And, at this moment, I disappeared down the rabbit hole of Marvell studies. Who is the coy mistress? Why had I never spared her a thought until this day? Why was I content to let her body function as a blank canvas for Marvell’s rhetorical emissions? She’s been hiding in plain sight for my whole adult life. I’ve smiled at her ‘coyness’ and my imagination fleshed out her ‘youthful hue’ pruriently.

But Scott asks us to look again. Her ‘youthful hue / Sits on [her] skin like morning dew’… How, I ask myself, can I have never seen this before? Or was it just that I was incapable of imagining it? I mean, if exam boards anthologize the poem, then she’s a women and not a child… Poking around JSTOR, it transpires that the disquiet surrounding ‘To His Coy Mistress’ predates #MeToo by more than a decade. In Michael John DiSanto’s article, ‘Andrew Marvell’s Ambivalence toward Adult Sexualities’ in Studies in English Literature, 1500 – 1900, he asks ‘whether our reading habits have made us blind to this problem, and whether a fascination with nymphets has become acceptable in our culture’. In The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography W.H. Kelliher writes:

“On Fairfax’s withdrawal to his native Yorkshire, Marvell was employed as tutor in languages to his twelve-year-old daughter Mary. It says much about his character and religious temper that her devoutly Presbyterian parents and formidable grandmother Lady Vere found him, in Milton’s phrase, ‘of an approved conversation’ (TNA: PRO, SP 18/33/75). By the winter he was praising his pupil in some English verses prefaced to the translation of James Primrose’s Popular Errors (1651) by the Hull physician Robert Witty.”

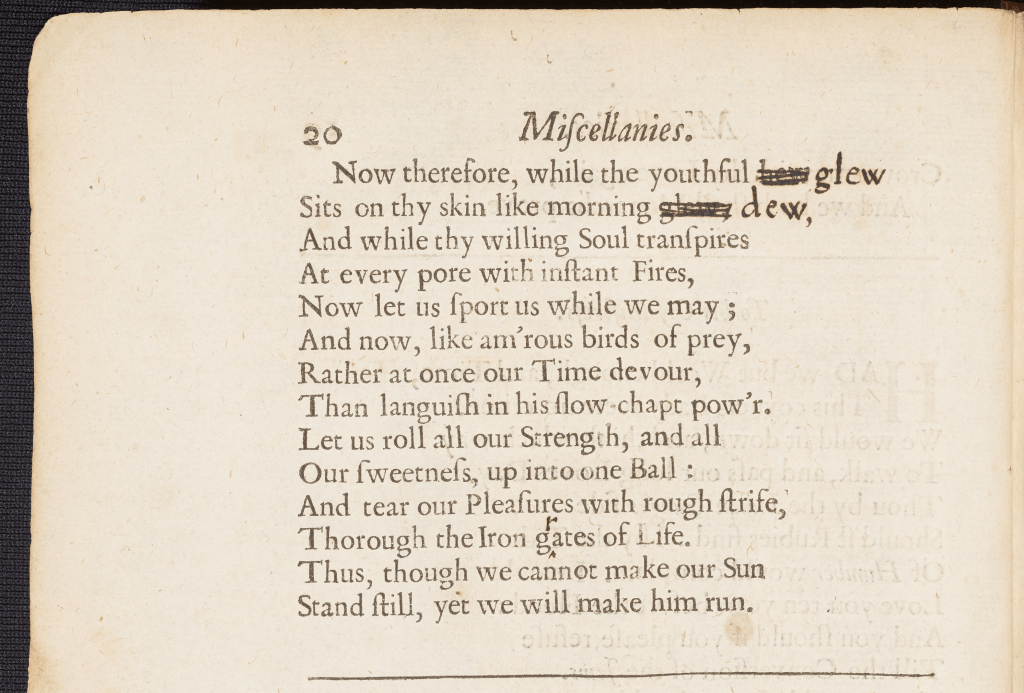

Okay. Deep intake of breath – and back to Scott’s ‘Coy’. He uses the modified spellings adopted by Helen Gardner in her The Metaphysical Poets. Scott’s speaker remarks on his ‘youthful hew / to ashes conversion’ where we might expect a ‘youthful hue’. While ‘hew’ is a variant of ‘hue’ – and this remains a possibility – we might also imagine a shout, an outcry, or perhaps even shaping with an axe. Meanwhile, in the Bodleian Library’s 1681 collection, the copyist doesn’t think ‘hew’ is right either, and alters it to ‘glew’ – mirth, rejoicing. Out with the dark and in with the light. Even the poem’s body is a battleground. Scott’s Coy Mistress continues, seeing herself as ‘his / prey, his found pleasures, skin-ball for his sport’. It’s all there on Marvell’s page but, once seen, Scott’s vocabularyclept cannot be unseen.

That Broke into Shining Crystals is ravishing. From page to page it delights with its riot of forms and witty, suggestive, intoxicating language. It’s confessional poetry at its finest and to read it is to receive a priceless gift.

Buy That Broke into Shining Crystals from uk.bookshop.org

RELATED LINKS

Read my review of Richard Scott’s Soho, commissioned by the T.S. Eliot Prize