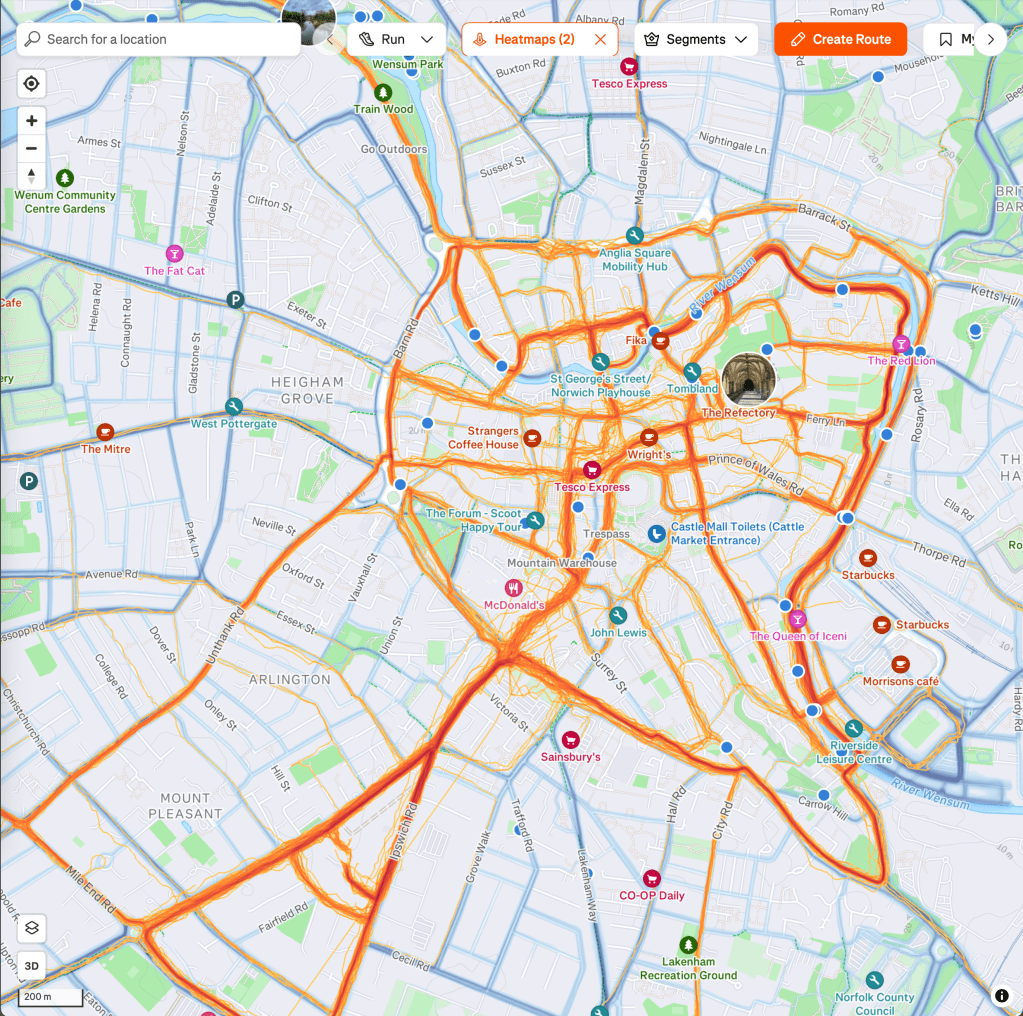

My three-year-old daughter accompanied me to John Lewis (though it would be more accurate to say that I accompanied her.) We’d bought the new shoes / whatever it was we needed, and wandered the aisles for a while before she asked whether I was lost. She told me not to worry, took me by the hand and led me to the exit. So, you’ll understand that when I relocated for work a few years ago, I wondered how my new city would ever feel like home. My superpower turned out to be running. Pounding the pavements by day and by night has helped me to internalise the city in a way that I would never have managed with a satnav and a handful of routes to supermarkets.

Charles Lang’s first collection, The Oasis, opens with a bang with ‘The Chase’: ‘Aw it takes is a wee ‘fuck the polis’ n a night ae excitement is on: / the chase, navigatin side streets n gable ends, hidin in bushes’. On a first reading, I imagined Irvine Welsh’s Edinburgh as seen through Danny Boyle’s eyes, Ewan McGregor running from the police to Iggy Pop’s punk rock ‘Lust for Life’, but Lang’s speaker’s bursting with joie de vivre. This isn’t a functional chase to fund a skag habit but ‘a night ae excitement’ – a full evening’s entertainment, and planned as such. Its impetus ‘is a wee ‘fuck the polis” – with the diminutive ‘wee’ adding a childlike (childish?), impish and endearing quality to the taunt. It’s not a crime at all. If the taunt is ‘wee’, then either the police are on a hair-trigger, their reaction grossly disproportionate or (and I like to imagine this as more likely) they are just as bored as the children and accept the opportunity for some excitement gratefully. Thrilling as it is, this is a calculated chase. The speaker and his pals are ‘navigatin’. They ‘map it was ease – the school, the wee shop, the tree swing, / the bought hooses, ma granny’s hoose, ma pal’s aunty’s hoose, the lane’. The definite articles point to the microscopic size of this world, a world with a single lane. The poem is structured in couplets, pointing to the weird intimacy between perp and polis but, instead of a final couplet, Lang leaves us with a half line: ”awright officers // wit yees been up tae the night?” It demonstrates the speaker’s power to pick up the polis and to put them down at will. As an opening shot, ‘The Chase’ pulses with life.

A couple of pages on, and ‘New Shoes’ illustrates that the apparent freedom of ‘The Chase’ is strictly limited. The speaker’s mother presents him with a new pair of white Lacoste trainers: ‘The rules ur as follows— // nae wearin them tae school, / nae climbin fences, nae games a hidey’. It’s exquisitely observed: that the trainers cannot be be worn to school suggests that the omniscient ma knows only too well that, for the sake of fashion and status, her son would swap his trainers for his school shoes at the gate and, whereas climbing trees evokes Boy’s Own adventures, the climbing of fences, their urban equivalent, has a different feel. Ma reels off her commandments, nae, nae, nae with rhetorical polish, omniscience and omnipotence. In ‘The Chase’, the children enjoy the last word… but here? The son knows better than to open his mouth.

The final section, ‘Glasgow Sonnets’, rings a more sonorous, melancholy note as it muses on Glasgow past and present and brings me back to my heatmap of Norwich. Navigating the M8 in central Glasgow makes my palms sweat and raises my pulse. On and off ramps are truncated. Vehicles enter and exit from both the left and the right. Congestion hides lane markings. The lines on my heat map represent points of contact between feet and street. They represent a deepening connection between person and place, whereas Lang visualises the M8 as a botched operation, a false hope: ‘Flyovers, wance the future, / dissect the city / n send it tae an early grave’. ‘The air is thick’ with the modern embodiment of a pea-souper, ‘n awready everybody / hus forgotten aboot Rosebank‘ and our attention spans struggle to extend much beyond the current news cycle. Like lab rats, we’re ‘going to root the inner/outer / circle in the dark’, like the denizens of Dante’s Inferno.

Lang’s powers of observation are forensic and, as a result, his poems ring with truth and radiate warmth. The Oasis is an affectionate portrait of a city and its people but tackles division and confrontation head-on.